Opinions

Notes from the Plains Pt. 1

3 Generations in North Dakota

Silence. The crack of wood against the taut skin of a medicine drum. A multitude of voices weave in and out of harmony and dissonance: a braid of beautiful human noise. Swathed in darkness, I hear the sharp hiss of water hitting red hot stones. Steam rises, engulfing my bare skin with its heat. Below me is cold ground. Above me, an intricately woven matrix of sticks, tied together with torn fabric and covered in heavy tarps, blocks out all light. This experience, of sitting in this sacred space, is one that I will never forget.

I’m privileged enough to be in a Hidatsa sweat lodge. I was invited by Edmund Baker, the environmental director for the Three Affiliated Tribes of the Mandan Hidatsa Arikara Nations, on the Fort Berthold Indian Reservation in western North Dakota. Three Generations’ relationship with Edmund began in 2014 prior to the filming of A Different American Dream. In the film, Edmund spoke of his concerns about the impact of oil fracking on the Fort Berthold Reservation. Now, five years later, filmmaker Jane Wells––with me in tow––has returned to North Dakota to follow up with the friends, collaborators and voices of 3 Generations who reside here.

From across the Atlantic in cold and rainy London, the Great Plains seemed a place shrouded in mystery and fascination. Images of expansive frozen landscapes, badlands, of tipis lining the banks of the Missouri River, of Native people––on horseback, collecting sweetgrass and sage for medicine ceremonies––all sprung to mind. This romanticized vision of the Great Plains is ubiquitous among those, like myself, who have never visited the region. Much of our contemporary non-Native understanding of First Nations culture is haunted by these stereotypes.

But it’s through experiences like being inside the profound darkness of Edmund’s sweat lodge, that I am able to see the powerful resilience of Native culture. The poorly rendered clichés are stripped away and I witness the complex, beautiful relationship between the MHA Nation and the land they inhabit, the traditions they have kept, and the way they fight for their culture in a country that has, since the arrival of Europeans, attempted to stifle and destroy their way of life.

Indigenous people of the Great Plains have been practicing the sweat lodge ceremony for thousands of years for the purposes of cleansing, healing, divining insight, and maintaining contact with their ancestors. It is a great privilege to be invited into one; Edmund’s invitation stands as a testament to the close relationship between him and 3 Generations.

Deeply concerned for the land his people inhabit, Edmund is committed to raising awareness about the harmful impact of the oil boom on the air that he and his family breathe every day and its wider implications for the environment we all share. He comes across as stoic, wise, and highly educated, yet he also possesses a deadpan sense of humour which reminds me of home.

“Today is the day that some guy apparently discovered this country a couple of hundred years ago,” he says with a wry smile. Edmund pauses for a moment. “I can’t quite recall his name.” It is, of course, Indigenous Peoples’ Day, the holiday still celebrated by most Americans as “Columbus Day.”

The following morning, we meet with Jayli Fimbres, a Hidasta activist and educator in her twenties. Jayli also appeared in A Different American Dream, and is now working tirelessly to sustain the language of her ancestors. The Hidatsa language thrived among the people of the Knife River until the arrival of white settlers. Violent colonial subjugation and outbreaks of disease from European pathogens, decimated indigenous populations. Hidatsa, Mandan and Arikara were forbidden and English was enforced as the primary language. The Hidatsa language suffered further destruction through the forced separation of Native families. Indigenous children were sent off to boarding schools, where they were punished for speaking their own language, and made to feel ashamed of their ancestral heritage.

There are now only approximately 100 Hidatsa speakers, most of whom are over 65. Jayli tells us that many of these Hidasta speakers are reticent to speak the language, as it triggers the traumas of the brutal boarding school system. “When you take away a people’s language,” she says, “you take away their identity, their sense of self.”

Language control is an age-old weapon of colonial violence, as noted by theorists like Ngugi Wa-Thiongo and Franz Fanon. Fundamental aspects of any culture reside in its spoken tongue: the importance of names; the relationship to the natural world; the nuances of metaphor and interpersonal communication; the vitality of humour. When a language dies, so does a vital part of its speakers’ experience.

Jayli takes us to the MHA Language centre, where we meet her mentor, Sally Going In the Water Woman, who is working with Jayli to refine her spoken Hidatsa so she can continue to teach the rich and complex Plains language.

This small team of activists, educators and enthusiasts, aim to return the Hidatsa language to the mouths of its rightful inheritors. “Zagitz,” Sally tells me, is a Hidatsa equivalent for the word “good,” though its meaning is wider than the simple English affirmation. It is “zagitz,” she says, to have young people like Jayli working to revive the language.

Since the filming of ADAD, Jayli has devoted her much of her spare time to becoming a cowgirl. She’s learning roping, and rides horses with her boyfriend, a local rodeo star. She’s also studying Jingle Dance, a traditional Native dance style, seen at Pow Wows all across the country. It’s extraordinary to see a young person, firmly rooted in contemporary life yet proudly devoted to preserving her heritage, working hard to right the wrongs inflicted on her people.

In Bismarck, North Dakota’s capital, we spend a few days with Dr. Biron Stands Above Baker. Originally a resident of Fort Berthold, his role in ADAD was fundamental.

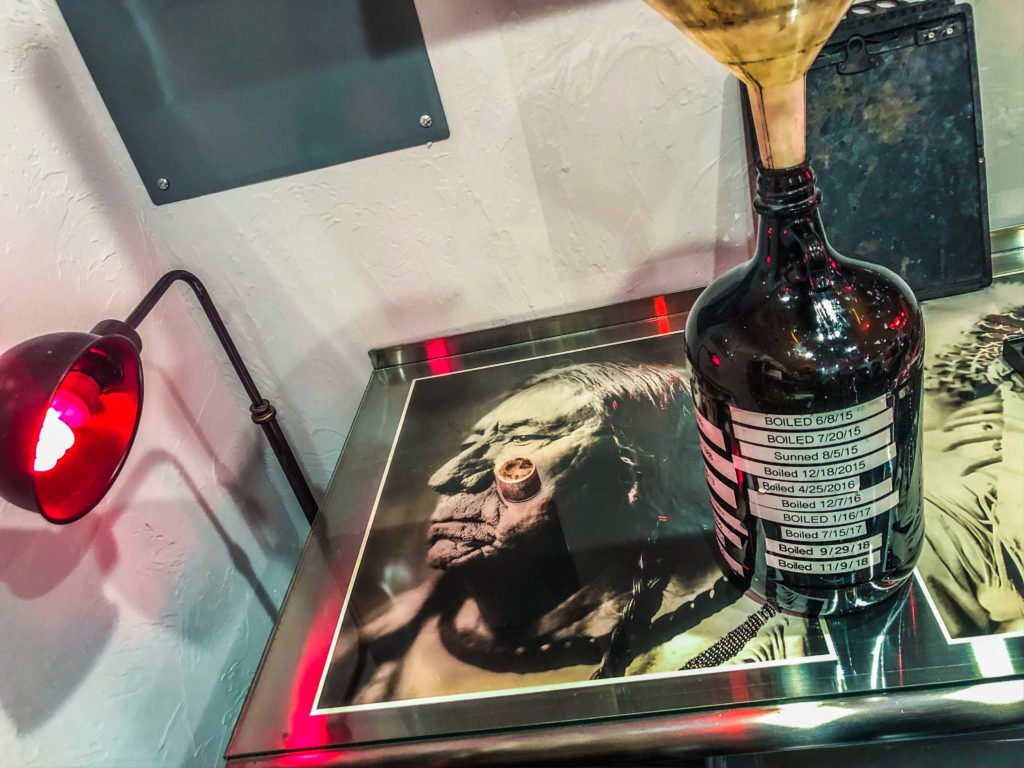

Amongst much laughter, and sharing of anti-Trump memes, we pay a visit to the studio of Shane ‘Shadow Catcher’ Balkowitsch, a traditional ambrotypist, who takes a portrait of Biron’s partner, Sheri Her Many Horses Woman. Balkowitch, using a wet plate technique developed in the 19th century, creates images cast on plate glass in oxidised silver. The images, which require a lengthy ten second exposures, seem to capture the essence of his subjects.

A week before our visit, Shane was asked to take a portrait of environmental activist Greta Thunberg, who had come to visit the Standing Rock Reservation and address the devastating impact of the Dakota pipeline. Humble, generous, and good humoured, Shane now sets aside an entire afternoon for us.

Shane’s portraits confront the viewer with their raw, unguarded humanity. In his ongoing project, 1,000 Plains Native Americans, he endeavors to capture portraits of contemporary Plains Natives. The oxidised silver images Shane creates last 1,000 years, ensuring that the faces and identities of the indigenous inhabitants of this region cannot be erased or forgotten.

In his studio, an image of Sheri emerges under the red light of the developing room; we see another face added to the series and gain a rare insight into his working process.

As we drive back through four feet of Great Plains snow, we pass the North Dakota Veteran’s Cemetery, stopping to pay our respects. Among those interred are many fallen Native American soldiers, who gave their service and their lives, in WWII, Korea, Vietnam, Iraq and Afghanistan. It’s an underreported fact that Native Americans serve the US military in greater numbers per capita than any other ethnic group. But they are represented and remembered here, among the thousands of solemn marble gravestones that punctuate the vast frozen plain.