Opinions

Notes from the Plains Pt. 2

3 Generations in Minnesota

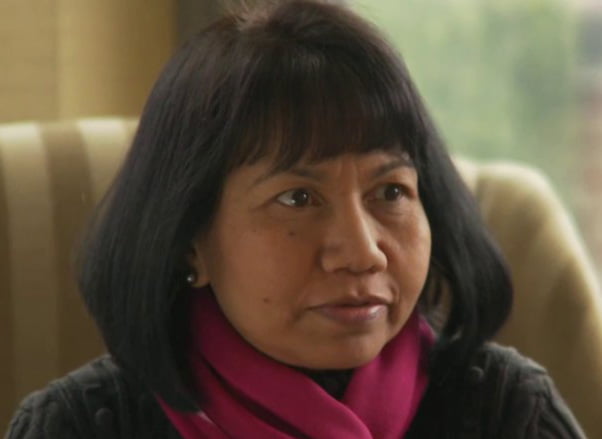

Across the state line in Minneapolis, the vibrant cosmopolis of the Midwest, we meet with Ojibwe social worker and activist Amy Arndt, who works with the Minnesota Indian Women’s Resource Center doing crucial work to rehabilitate Native female victims of abuse and sex trafficking. Amy and Jane worked together on the development and production of Native Silence, 3 Generations’ 2013 film, which addresses the issue of sex trafficking in Native communities. Native women are over 2.5 times more likely to experience sexual assault or abuse than non-Native women, according to data gathered by the US Department of Justice. It’s probable, Amy tells us, that the actual figures are far higher than those reported.

We meet Amy’s daughter Alex, who has taken up the mantle of pursuing justice and reconciliation for young Native people, working at Ain Dah Yung Center in St. Paul, Minnesota, a youth organisation which provides a vital touchstone for the young Native population of the Twin Cities.

Alongside confabbing about our shared love of Minneapolis superstar Prince, Amy and Alex discuss the complex intersections of what it means to be Native, female, urban, and American. They take us to visit Birchbark Books & Native Arts, the iconic bookstore opened by award-winning Ojibwe novelist Louise Erdrich. It’s a hub of creativity and literary culture in Minneapolis.

Like Erdrich, both Alex and Amy are actively involved in preserving and proliferating the acknowledgement of their Native heritage in the Twin Cities. They observe traditional ceremonies, are deeply knowledgeable about Native American history, and are tuned in to the contemporary political landscape. They also drink good coffee, know the city inside out, and regularly attend drag shows.

Over in St Paul, we visit Amy’s mother Joyce, one of the principal subjects of Native Silence. Joyce’s background, of forced removal from her family at a young age and a battle against addiction, led her to a career as a nurse. She is a beacon of hope within her community.

Joyce has recently moved to Elders Lodge, a supportive, affordable housing organization for Native elders, built in the shape of a soaring eagle. The Lodge, where turkeys roam in the backyard, holds regular ceremonies and offers daily Native art and craft activities, the products of which decorate the walls.

Joyce speeds over to us on her motorised scooter, singing Steppenwolf’s “Born to Be Wild.” Her purple hair complements the red maple trees that line the Lodge’s grounds. Showing us around, she gleefully tells us how relieved she is to have moved to a culturally specific home, where she can pursue her talent for painting and be part of a community who not only share her ancestry, but much of the historical trauma that comes with it. Here, they are safe to heal and grow together. She also isn’t far from Amy and her grandchildren. Between Joyce, Amy and Alex, it’s hard not to notice the symbolism; three generations of Ojibwe women, working tirelessly in their communities to bring about change.

On my final day before leaving Minnesota, Alex takes me to Little Earth of United Tribes, a HUD-subsidized housing complex in central Minneapolis, and the only American Indian specific Section 8 rental assistance community in the United States. Like many deprived urban environments in America, Alex tells me, Little Earth suffers from social problems, and can be dangerous. But for its 1,000 or so residents, it is home. Little Earth fosters community projects, social programs, elder services and health initiatives, including the one at which Amy works.

Adjacent to the Minneapolis American Indian Center on Franklin Avenue sits a bright yellow building, painted with colourful murals. This is All My Relations Gallery, a space for contemporary Native art. AMR gallery focuses on “the contemporary American Indian experience in all its diversity,” while preserving “the living influence of preceding generations.” It seeks to defy the clichéd souvenir-store notions of what constitutes “Indian Art.”

Passing through the cafe which serves traditional Native dishes, we enter the gallery space. The current exhibition is entitled “Changing Horizons,” and celebrates the influence of George Morrison, who was, in his own words, “an artist who just happened to be an Indian.”

Walking through the exhibition, I’m struck by the vision of these contemporary Native American artists of the Twin Cities. Their work honours the rich artistic traditions of their ancestry, without wishing to be defined by it. Much of the history of Indigenous Americans has been decided by outsiders who sought to conquer and exploit. The art on the walls around me is testament to the power of reclaiming a voice that has been, and often still is, stifled, manipulated, and silenced by mainstream America.

The myths, stereotypes and clichéd representations of Native American culture remain rife in American society, as well as here in Europe, where curious onlookers struggle to make sense of the deep wounds carved into the Native story ever since the arrival of “that Christopher Columbus guy.” Reductive, New Age platitudes about “Native wisdom” now intersect with the grim specters of racism, colonial subjugation, and historical injustice.

The diverse array of individuals I was lucky enough to meet through Three Generations continue to preserve their ancient traditions and confront the historical trauma and injustice of their past.

There are still difficulties and discrimination from a systemic pattern of subjugation and indifference, but what I saw here was hope. The Indigenous culture of the Plains is alive, and like the sacred medicine songs I heard in the sweat lodge, their voices grow ever louder in the darkness.